Click for PDF

Early Modern Studies Journal

English Department | University of Texas | Arlington

Practical Paleography and the Baumfylde Manuscript: An Undergraduate Research Unit for Literature Classes

Keri Sanburn Behre, Portland State University

My Early Modern Literature and Culture class, subtitled “Shakespeare’s Sister,” is themed on the idea of the fictional woman conjured by Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own. Woolf evokes the character, whom she calls “Judith,” to illustrate the myriad ways that women writers have been rendered invisible throughout history. Aided by the theoretical approach of the “hidden transcript,”[1] the class uses reading, writing, commonplace books, and our own curiosity and experiences to delve into the complexity of early English literature written by and for the early modern women who were Shakespeare’s contemporaries. This article contains a detailed account of my first time teaching the paleography unit I created for this class as well as some reflections on the pedagogical importance of practical paleography—that is, transcribing manuscripts with enough precision and comprehension that the recipes can be followed by the transcriber. The unit is centered on the Baumfylde Va 456 manuscript (1626, 1702–1758), a collection of medicinal and culinary recipes begun by Mary Baumfylde in 1626 and continued in several other hands into the eighteenth century. While the manuscript is housed at the Folger Shakespeare Library, it is fully available online to the public. The paleography lessons described here would work well in any class in which three weeks could be devoted to a study of the manuscript, basic transcription skills, and the material culture of the period. Working with the Baumfylde manuscript introduces valuable literary diversity by showcasing women writers and engendering conversations on what constitutes a literary text. Transcribing and editing its recipes with the goal of creating the foods and medicines they describe brings to students a scholarly degree of close reading, immersion, and material participation not easily achievable through more traditional modes of study. Teaching the Baumfylde manuscript allows students to exercise practical transcription and interpretation skills while inviting them to participate in the concept of literary self-creation by contributing to a unique transcribed edition of the text based upon their experiences.

Pedagogical Considerations

For the students, transcription was an empowering and satisfying form of engagement with an unfamiliar text. It provided them with the opportunity to read closely, interpret contextually, and experience the satisfaction of making a practical text and the material history of the period they were studying more available to their classmates, friends, and families. Moreover, close study of a medicinal and culinary recipe manuscript brought an often-overlooked body of women’s writing to the students. Rebecca Laroche argues that

if female-authored texts are to gain equal footing in the discussion of early modern English culture, the terms of inquiry must change. Whereas discussions of literary traditions as established by nineteenth-century scholars continue to keep sixteenth- and seventeenth-century female writers in belated or marginal positions, I believe that analysis with an eye toward herbal content may uncover interesting potentials in works by writers of either gender.[2]

The herbal knowledge to which Laroche refers is not a common basis of analysis in literary studies, but it is critical to understanding both medicine and cooking in the early modern period. Life writing, including recipe books, thus not only represents an opportunity to introduce genre variation into the body of early modern women’s literature that students encounter, but also encourages and even necessitates deepening our engagement with texts that have not yet been fully explored.

As Catherine Field argues, early modern culture held the idea of “selfhood” for women as an undesirable trait that represented an inability for self-governance.[3] Therefore, women had to be strategic if they wanted to write about themselves. Field has also convincingly argued that recipe book manuscripts should be considered as a type of self-expression, a safe place of confluence between the rules of the time and the opportunity to work on self-making. Consider further that recipe-writing was a way for women to simultaneously inhabit both the private sphere of the household, to which they were relegated by conduct manuals and general expectation, and the public sphere. Their writing represented conscious and cultivated versions of themselves that, by excluding (or at least occluding) their bodies, could achieve a respectable publicness that would not otherwise be allowed. Martine Van Elk argues that English marriage manuals offered “mixed frameworks for understanding the opposition between public and private.”[4] Recipe-writing takes advantage of these mixed frameworks. Certainly there were many women for whom it would have been unacceptable—impractical, indulgent, laughable—to sit down and create poetry or drama. For them, writing recipes might have provided a deeply fulfilling creative outlet. Given these ingrained social attitudes, we can see the recipe book as a more democratic literary form, available to a somewhat broader socioeconomic range of women. Elaine Leong points to Gervase Markham’s The English Housewife as evidence of the expectation that married women would be medical practitioners knowledgeable in the administration of surgery and the creation of medicines.[5] Markham called it “one of the most principal vertues which doth belong to our English Housewife.”[6] By claiming the authority to which they were rightfully entitled within the private sphere, the sharing of household recipes between women becomes inscribed as a prosocial activity that supports the status quo while providing the opportunity for creativity and self-expression.

In order to help students understand the historical context, I engage them in discussions about the controversy surrounding both the authority of women’s writing and the legitimacy of women’s medical practice. Our attention to women’s authorship intersects with discussions of recipe books and other manuscripts, and the exclusion of women from “professionalism” in both literary and medical worlds is a rich area of inquiry.[7] While male-authored printed recipe books were a flourishing genre with origins reaching back to 1500, women circulated their recipes almost exclusively in manuscript form.[8] As professional medical authority became more and more vigorously defended after the Restoration, the medical literature demonstrates the tightening controls on traditional medical practitioners, many of whom were women.[9] In the 1665 work Loimologia: Consolatory Advice, And some brief Observations Concerning the Present Pest, George Thomson begins with an admonishment that legitimate physicians like himself should hide their remedies “lest they be vilified and disesteemed by the vulgar, who are ready to spurn at, and tread upon the most precious things.”[10] Unlike earlier public health pamphlets, the majority of the tract is characterized by the anxiety that his medical knowledge will be stolen and misused; Thomson spends significant space denouncing illegitimate practitioners and praising legitimately trained physicians.[11] The rhetoric of this text clearly demonstrates the growing power—and anxiety—of the exclusively male medical industry. Laroche observes that the emergent medical model based in “the physician-surgeon-apothecary set of practitioners” sought to erase and illegitimize the long and rich tradition of female medical practice.[12] This suggests that for women to keep a recipe book filled with medical recipes may have been a somewhat subversive act, while at the same time being quite common.

Contextualizing the Unit

Preceding this unit on the Baumfylde manuscript, students in my ten-week LIT 379: Early Modern Literature and Culture course spent seven weeks studying early modern women’s literature and literary contexts. We began by studying theoretical and historical contexts, including a unit on “Writing For Women” (excerpts of conduct and instruction manuals, including Chapter 1 of Gervase Markham’s The English Housewife). We read Ruth Goodman’s accessible How to Be a Tudor: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Renaissance Life,[13] choosing sections on which to present, and the students start their term-long “commonplace book” assignments[14] as a way to practice early modern reading and writing habits. From there, we devote three weeks each to poetry and drama by early modern women.

For this final unit on our syllabus, I began by defining paleography—the study, deciphering, and dating of historical writing and manuscripts—for students. In order to access texts that are not readily available in edited form, we need to learn to read them, and that means getting comfortable with what initially looks to many of them like handwriting in another language. I was careful to introduce the project gently with a less-challenging recipe, but was surprised by how many students jumped in eagerly, collaboratively deciphering the manuscript without any initial direction from me, and supporting one another in their efforts. In this way, I found that the recipes functioned as “affective objects,” a term Dianne Mulcahy uses to describe materials that engage students by shaking their assumptions about the work they will encounter in the classroom.[15] In this case, students encountered an unusual text and engaging deciphering activity that shook awake their assumptions about the work we do in an early modern literature class. In future classes, I am eager to experiment with this manuscript unit first, before we study women’s poetry and prose, as I anticipate that it could positively alter students’ relationships with the texts that follow.

Before I gave the unit assignment, I asked students to consider how we might think about something like an early modern recipe, or “receipt” book—which may not immediately strike us as literary—as literature. Upon close examination, this kind of writing presents ample opportunity to consider the same questions of authorship, authority, and self-construction on the page that we are accustomed to thinking about in other forms of literature:

Like commonplace books, recipe collections muddy the line between authorship and ownership since owning the book and compiling it (with the help of friends, family, and other texts in manuscript and print) made the owner the ‘author’ of the text as she generated her writing out of the texts and practices of others and as she derived authority from her established place in the house.[16]

Considering these issues, the move from studying early modern women’s poetry and drama to the seemingly more prosaic forms of writing seen in the Baumfylde manuscript felt less jarring and more congruent. In the prior units, students had become involved in thinking about the layers of challenges faced by widely recognized women writers in the period, and how they surmounted those challenges; with the transcription unit, they got to consider how those challenges applied to women who may not have self-defined as “writers,” but still used writing for self-expression in the course of carrying forth their household duties. Students—approximately 50% English majors taking the course for an early British literature requirement, another 25% English majors using the course as an elective, and the final 25% nonmajors interested in the topic—connected quickly with the text, asking questions about the everyday literacy and writing practices of the women who wrote the Baumfylde manuscript and others like it. Thinking about it in this way, we began to appreciate the different but parallel ways that recipe-writing served early modern women and their goals: allowing a construction of the self as an expert and showcasing their authority in their daily activities of cooking and medicine.[17] As we studied this context, we discussed how we might come close to reconstructing the “sense of self” these women had as writers, cooks, and healers. And as we moved toward selecting and transcribing recipes that we intended to prepare, as I discuss below, we encountered a deeper level of close reading that immersive research demands.

By discussing issues of production, authorship, and authority, as well as the unique ownership women were able to take of issues of food, eating, and medical care, students came to a more comprehensive understanding of the text as literature. The manuscript invites us to consider these issues:

Mary Baumfylde signs, titles, and dates her receipt collection, ‘Mary Baumfylde her booke June Anno 1626,’ and she writes the phrase ‘many hands hands,’ and copies it several times down the middle of the page. This phrase with its repetition of the word ‘hands’ signifies and enacts its meaning of multiplicity, and following Baumfylde’s signature and repeated epigraph, the book’s subsequent owners also sign their names: ‘Master Abraham: Sommers,’ ‘Katherine Toster July 1707,’ and ‘Katherine Thatcher 1712” (possibly Katherine Toster’s married name, according to Field).[18]

As we discussed the front page and considered the “many hands hands” phrase as a broad attribution of shared intent, shared authorship, and shared experience, a student noted that the phrase begins to feel like an invitation to participate: reading the recipes, following their instructions, making notes and records of those experiences, and writing themselves into the history of the process.

Transcription Tutorial

For the unit assignment, I asked the students to work together to transcribe selected recipes of Medicinal and cookery recipes of Mary Baumfylde. I prepared them to experience some disorientation as they began transcribing, but reassured them that with patience, perseverance, and a recursive approach they would begin to discern letters and words. We began by completing a “transcription tutorial” designed to introduce the manuscript and the practices of manuscript transcription that would be necessary.

For the tutorial, I selected and excerpted recipes for transcription that I believe hit the correct difficulty level for beginner transcribers.[19] Students read English Handwriting, 1500–1700: An Online Course, “Basic Conventions for Transcription” in preparation for class the day of the tutorial. In practice, most of my students found the selected recipes somewhat easier than I had anticipated (perhaps due to the collaborative nature of the work). This had a positive overall effect on their confidence and ambitiousness as we moved into the next phase of the assignment, so I will maintain the tutorial at this level the next time I teach the unit.

The tutorial could take many shapes dependent on the course modality, time available, and faculty preference. I put students into small groups with printouts of the images and instructed them to work on the recipe transcriptions together, prior to going through them in class. This worked well, but for purposes of efficiency I may try giving the images as homework for independent transcription and later discussion and collaboration. In considering presenting this material in an online or hybrid class, I practiced setting some of the examples up in a Canvas quiz module, complete with images and fill-in-the-blank answers for key words in the early questions, working up to full lines in the later questions, where students would be prompted to keep trying until they submit the correct answer. This worked well, and would be easily reusable in subsequent terms, compensating for some of the setup work the first term. It does, however, lack the group collaboration of the in-class options, so a Google Doc “wiki” might be a more appealing alternative for online classes.

Assignment Details

The purpose of the tutorial stage was to build confidence in the manuscript, which they were already enthusiastic to explore as the focus of their collaborative class edition. Initially, I had planned to select the recipes for the class to follow in order to prevent overwhelming students with the manuscript, but I found that students wanted to explore the larger manuscript and to create a relationship with it by reading the recipes to which they felt the most drawn. Because of this, I made a last-minute decision to “turn them loose” in the manuscript, so to speak, after they had some successful transcription experiences with the tutorial. Myra J. Seaman argues that teaching students noncanonical texts helps them to develop their interpretation skills through forging relationships with texts that are less mediated by faculty interpretation: “Working without the net of the canon freed them to respond without a sense of what their response ‘ought’ to be.”[20] My decision to step out of the way and not be an intermediary for the text paid off: this practice produced the most inspiration, depth of engagement, and authentic connection to the text. Seaman’s findings suggest yet another reason to consider beginning the class with this unit, rather than ending with it, and I plan to try this next time I teach the class.

After the tutorial, each member of the class nominated several favorite recipes for inclusion in a collaborative class edition. I asked the students to rank their nominations in order of preference, as I correctly anticipated some overlapping requests. I allowed them freedom to choose culinary or medicinal recipes they were personally interested in transcribing, researching, and preparing, but decided to take alcohol-containing recipes (in which there was a strong surge of interest!) off the table in observation of campus rules. The final lineup for the class edition included the following recipes: “to make biskett,” “to make sirrupe of violetts,” “to preserue apricocks, or any other greene fruite,” “good for the face or hands,” “to make cheese cakes,” “another way to make cheese cake,” “an orang pudding,” “to stew mushrooms,” “to pickle wallnuts,” a second “to make biskett,” and “penny worth mallow leaves.” After the nomination process, I assigned each participant as the primary editor of one recipe and an associate editor of two additional recipes. In this way, each recipe in our class edition received multiple transcriptions and opportunities for correction before being finalized by its primary editor. Students then embarked on their three transcriptions, encountering the expected puzzlement, occasional frustration, and ultimate triumph of deciphering a difficult word or learning what it meant.

To set students up to decipher and research ingredients, answer questions, and make their own discoveries, it was helpful to have the following reference books available in either in the classroom or on reserve at the library:

- English Handwriting, 1500–1700: An Online Course, especially “Basic Conventions for Transcription”

- Gerard’s Herbal (This is available in a PDF here and through Archive.org, but I find my paper copy eminently more navigable, and it is satisfying and delightful for students to page through)

- Joan Fitzpatrick’s Shakespeare and the Language of Food

- Alan Davidson’s The Oxford Companion to Food

- Prosper Montagne’s Larousse Gastronomique

- Gervase Markham’s The English Housewife.

I also assigned Leong’s “‘Herbals She Peruseth’: Reading Medicine in Early Modern England” as required reading. This article served as a springboard to think about the Baumfylde manuscript and enriched our discussions as well as connecting the manuscript with the broader questions we had hitherto been engaging in class.[21] This phase of the project was more rigorous, challenging, and rewarding than I had anticipated. Erin I. Mann argues that foregrounding the material aspects and physical realities of book production in a “history of the book” class prior to introducing academic theory, history, and bibliographic scholarship results in better student engagement and outcomes.[22] Rhonda L. McDaniel suggests that haptic approaches to digital manuscripts in the classroom deepen student learning by attuning them to the material, textual, and physical aspects of medieval manuscripts, promoting “higher-level thinking and critical perspective in the college classroom.”[23] In the case of this project, as soon as students and I were faced with preparing the recipes we had transcribed, our curiosity, investment, and commitment to accuracy were awakened to a degree that I have not experienced in the absence of material engagement. Students were both making essay-worthy textual arguments with their associate editors about differing interpretations and going to heroic lengths to help one another interpret and understand difficult words. It was remarkable and worth noting that the text became real even before students experienced the products: the anticipation of the task of following the recipes dramatically changed our reading practices.

Next, students followed the recipes to which they were assigned as primary editor, brought them in to share with the class, and used their experiences to correct, augment, and finalize their annotations. Students commented that preparing to make the recipes inspired them to dive back in to “finished” transcriptions to make sure they were just right. They were particularly delighted by a delicious cheesecake made from fresh milk (“to make cheese cakes”), apricot preserves (“to preserue apricocks, or any other greene fruite”), and an egg-based hand cream (“good for the face or hands”) that worked spectacularly but, as we learned the next class period, spoiled rapidly in their classmate’s refrigerator. I encouraged students to keep explanatory notes relevant and focused on context and practice, and most were able to do this thoroughly. By the end of the project, each student had produced a single annotated edition of their recipe from the three transcriptions produced by the class. I compiled these and distributed them as a packet, but next time I will plan to publish them as a digital edition complete with pictures of their recipes so that the students can share their work with family and friends more readily.

Project Outcomes

We concluded the term with a reflection on the experience that included connections students were able to make between Mary Baumfylde’s recipe book and the rest of the material we studied in the class, both canonical and non-canonical. Students spoke enthusiastically about their relationship with the text and its authors. At the end of this project, students had increased confidence and skill in deciphering early modern handwriting. They finished the unit with a sense of having contributed to the field by making an interesting text more available and engaging. Some students may choose to participate in EMROC’s Transcribathon, where they will have the experience of knowing that their work can be a real, and lasting, contribution to making available the writing of early modern women. For me, this brings the project full-circle to the outcomes of my class on early modern women. Leong highlights the importance of material activities “such as nursing and caring, the dressing of wounds, the administering of foods and medicaments and the making of drugs,” and an appreciation of these daily activities brings the life of early modern within closer reach.[24] The most powerful outcome for both my students and for me was the connection to the manuscript’s authors, our own surroundings, and the material culture of the period from having investigated and prepared actual recipes from the manuscript. I write specifically about my own experiences transcribing and preparing a simple poultice recipe in an Early Modern Recipes Online Collective blog post entitled “Cooking in the Baumfylde Kitchen.” My activities—transcription, research, and material engagement—with the recipe and its components exemplify the value of this kind of activity. My students and I enjoyed thinking about Mary Baumfylde participating in what Leong calls the “reading and writing practices in the transfer and codification of early modern natural knowledge.”[25] Returning to the concept of the “hidden transcript,” students reflected upon the text as a palimpsest, and discussed the richness beneath the surface of that which might seem mundane at first glance. The day-to-day activities of most women’s lives would have involved these literacies and epistemologies, and commonplace engagements like writing and preparing recipes offered them inconspicuous opportunities for self-actualization. Focusing on these practices in a class acknowledges the creative work of early modern women. Achieving a material experience of this kind of work gives dimension and purpose to our study.

Appendix A: Materials for Transcription Tutorial

I selected these recipes to be an achievable difficulty level for beginner transcribers while providing a variety of hands and representation of both culinary and medicinal recipes. See the above section entitled “Transcription Tutorial” for ways you might use these materials in campus, hybrid, or online classes.

Almond Cakes

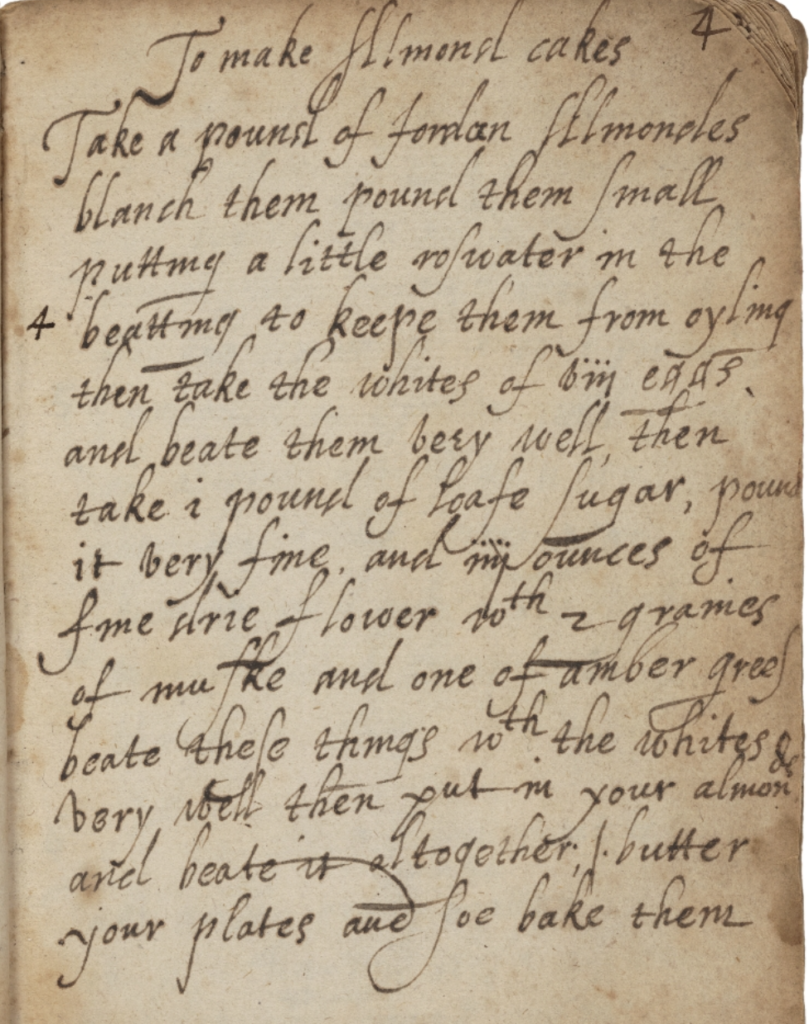

[Figure 1: 4r]

To make Almond cakes

Take a pound of Jordan Almondes

blanch them pound them small

putting a little roswater in the

beatting to keepe them from oyling

then take the whites of viii eggs,

and beate them very well, then

take i pound of loafe sugar, pound

it very fine, and iiii ounces of

fine drie flower w[i]th 2 graines

of muske and one of amber grees

beate these things w[i]th the whites

very well then put in your almonds

and beate it altogether, butter

your plates and soe bake them

White Hippocras

To make white Hippocras

Take a quart of white wine and put

into it iiii ounces of Synamon

brused and halfe an ounce of mace

iii nuttmeggs and halfe a pound of

fine sugar, and let it steepe 24

howers, then take a jelly bagg, and

put a little fresh Synamon in the

bottome of it, and 2 or 3 slices of

ginger, then take a pynt of new

milke, and power a little of the

milke and a little of the wine

and soe power it often through

the bagg, until it be cleare

To Heal A Bruise

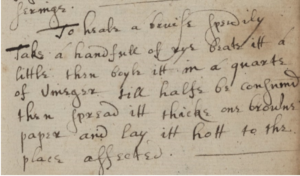

[Figure 3: 28r]

To heale a bruise speedily

Take a handful of rye beate itt a

little then boyle itt in a quarte

of Vinegar till halfe be consumd

then spread itt thicke one browne

paper and lay itt hot to the

place affected.

Poultice

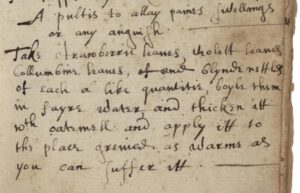

[Figure 4: 29r]

A pultis to allay paines swellings

or any anguish.

Take strawberries leaues, violett leaues

Collumbine leaues, of and blynde nettles

of each a like quaititie, boyle them

in fayre water, and thicken itt

w[i]th oatemell and apply itt to

the place grieued as Warme as

you can suffer itt.

Whey Drink

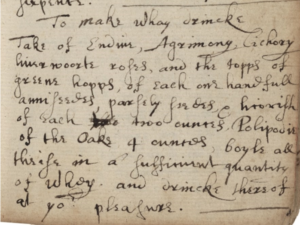

[Figure 5: 32r]

To make whay drincke

Take of Endiue, Agrimony, Cichory

liverwoorte roses, and the topps of

greene hopps, of each one handfull

anniseedes, parseley seedes, & licorish

of each two ounces, Polipodie

of the Oaks 4 ounces, boyle all

theise in a sufficient quantity

of whey. and drincke thereof

at your pleasure.

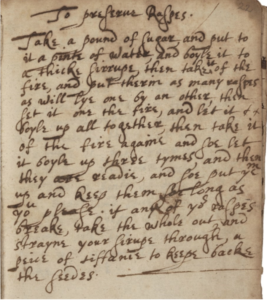

To Preserve Raspes

[Figure 6: 22r]

To preserve Raspes.

Take a pound of sugar, and put to

it a pinte of water, and boyle it to

a thicke sirrupe, then take it of the

fire, and put therein as many raspes

as will lye one by an other, then

set it one the fire, and let it tt

boyle up all together, then take it

of the fire againe and soe let

it boyle up three tymes, and then

they are readie, and soe put [them]

up and keep them for long as

you please. if any of y[ou]r raspes

breake, take the whole out and

strayne your sirupe through, a

piece of tiffanie to keepe backe

the seedes.

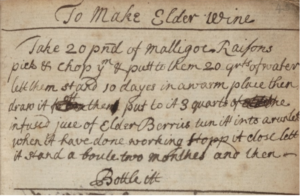

Elder Wine

[Figure 7: 45r]

To Make Elder Wine

Take 20 pnd of malligoe Raisons

pick & chop [them] and putt to them 20 [quarts] of water

lett them stand 10 dayes in a warm place then

draw it off then put to it 3 quarts of the

infused iuice of Elder Berries turn itt into a runtlet

when it haue done working stopp it close lett

it stand a boute two monthes and then

Bottle itt.

For Scalding or Burning

[Figure 8: 25r]

ffor scaldinge or Burninge to keepe itt

from blisterringe.Takea stronge onion, and as much Bay

salt & beate them well together and

apply itt to the soare place. & itt helpeth

Take onions and bay salt of each

a like quantitie, beat them well

together, and streine itt: wett cloath

therein and apply itt them to the

place grieued.

Appendix B: Discussion Questions

As we moved through the phases of the tutorial and assignment, I used these discussion questions to keep students focused on the larger issues of the manuscript as a form of literature:

- How can we reconstruct Baumfylde’s “sense of self” as a writer? How can we come close?

- Where, specifically, do we have evidence of Mary Baumfylde performing her engagement with the conventions of the receipt book?

- Where and how is she consciously representing herself and her book?

- In what ways does she claim authority over the recipes presented, the knowledge about the body put forth?

- What is the value in actually preparing/trying the recipes?

- How does the manuscript nature of this text impact our perception of her authorship?

- Gervase Markham ascribes his medicinal recipes to a private manuscript compiled by a skilled lady. What does this tell us about authorship, authority, expectation?

- How did this genre give women an opportunity to claim agency, authority, or power?

Appendix C: Commonplace Book Assignment

Keeping a commonplace book, or “commonplacing,” is an historical literary art that dates back to the middle ages, but was particularly popular in the early modern period, especially (but by no means exclusively) with women. We will practice this historical literary art as we move through the class.

To begin, you will need a notebook that appeals to you. This can be as fancy or simple as you like, and may be any size you find comfortable to write in (historically, most commonplace books were closer to pocket-sized than legal-sized, but any size will work for our purposes). Many students will choose to purchase something special for the assignment, but if you have something that works for you, that is perfect as well.

Keep your notebook at hand as you read through the assignments for this class, copying at least two excerpts from each assigned reading or author (as instructed) by hand and then writing a paragraph-long reflection on the excerpt you copied. Between reading sessions, I encourage you to keep notes of related thoughts (whether it’s something interesting you note from the course, an idea for your critical essay, or a relevant thought or connection that occurs to you). You may draw in your book or paste in images if you like (though these things are not required). Basically, this notebook will serve as a unique intellectual (and possibly artistic) record of your journey into the world of “Shakespeare’s Sister” through culture, history, and, most importantly, literature.

It is important to stay on top of this assignment! To help you do so, I will require you to share your books briefly during class throughout the term.

Please include a one-page reflection on your process of commonplacing, addressing the following questions:

- What was it like for you to shift to such an analogue form of note-taking? Did you find your creativity coming out in unexpected ways?

- How did commonplacing impact your processing of the information you wrote about? What insight into the reading and writing habits of the early modern woman, writer, or scholar did this exercise impart to you?

- Which are your the three best entries, and why are they the best?

- Overall, what did you learn from the experience? Will this change your note-taking methods in the future, and if so, how?

- At the end of your reflection, include a Table of Contents, organized either by date or page number. In it, identify the top three annotations you mentioned in your reflection with an asterisk or some other marker.

Keri Sanburn Behre is a full-time Senior Instructor at Portland State University in Oregon. Her research focuses on the intersections of early modern literature with food, medicine, and gender. She has published such articles as “‘Look What Market She Hath Made’: Women, Commerce, and Power in A Chaste Maid in Cheapside and Bartholomew Fair” in Early Theatre and “Cooking in the Baumfylde Kitchen” on the Early Modern Recipes Online Collective Blog.

Notes

[1] James C. Scott, Domination and the Art of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven, 2008).

[2] Rebecca Laroche, Medical Authority and Englishwomen’s Herbal Texts, 1550-1650 (Ashgate, 2009), 9-10.

[3] Catherine Field, “‘Many hands hands’: Writing the Self in Early Modern Women’s Recipe Books,” in Genre and Women’s Life Writing in Early Modern England, ed. Michelle M. Dowd and Julie A. Eckerle (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007), 49-50.

[4] Martine Van Elk, Early Modern Women’s Writing: Domesticity, Privacy, and the Public Sphere in England and the Dutch Republic (Palgrave Macmillan, Springer International Publishing AG, 2017), 39.

[5] Elaine Leong, “‘Herbals She Peruseth’: Reading Medicine in Early Modern England,” Renaissance Studies: Journal of the Society for Renaissance Studies 28, no. 4 (Sept. 2014): 556.

[6] Gervase Markham, Covntrey Contentments, OR The English Husvvife. CONTAINING The inward and outward Vertues which ought to be in a compleate Woman (London, 1623), 8. From the Library of Dr. and Mrs. John Talbot Gernon, The Lilly Library, The University of Indiana.

[7] Catherine Morphis discusses women’s practice of reproductive medicine at length in “Swaddling England: How Jane Sharp’s Midwives Book Shaped the Body of Early Modern Reproductive Tradition,” Early Modern Studies Journal 6 (2014): 166-194. Laroche and Georgianna Ziegler curated Beyond Home Remedy: Women, Medicine, and Science at the Folger Library (2011), chronicling significant contributions women made to early modern medicine.

[8] Field, 50.

[9] Ole Peter Grell and Andrew Cunningham, introduction to Religio Medici: Medicine and

Religion in Seventeenth-Century England (Brookfield, Vermont: Ashgate: 1996), 7.

[10] George Thomson, Loimologia: Consolatory Advice, And some brief Observations

Concerning the Present Pest (London: L. Chapman, 1665), 1.

[11] Thomson, 15.

[12] Laroche, 4.

[13] Ruth Goodman, How to Be a Tudor: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Renaissance Life (New York, Liveright, 2016).

[14] See Appendix C for assignment.

[15] Dianne Mulcahy, “Affective assemblages: body matters in the pedagogic practices of contemporary school classrooms,” Pedagogy, Culture, & Society 20, no. 1 (2012): 16. Mulcahy uses actor-network theory to argue that affect, constructed through a complex set of “materiality and matter,” profoundly impacts the classroom and can be channeled for more effective learning.

[16] Field, 54.

[17] Field, 54.

[18] Field, 54.

[19] See Appendix A for full text of tutorial, including images.

[20] Myra J. Seaman, “Medieval Prime Time: Entertaining the Family in Fifteenth-Century England – and Educating Students in Twenty-First-Century America,” Pedagogy 13, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 222.

[21] See Appendix B for discussion questions.

[22] Erin I. Mann, “Doing More, Reading Less: Revising History of the Book Pedagogy,” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Teaching: SMART 25, no. 2 (2018): 35.

[23] Rhonda L. McDaniel, Manuscripts in the College Classroom: Material and Virtual Pedagogies,” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Teaching: SMART 25, no. 2 (2018): 25.

[24] Leong, 559.

[25] Leong, 560.