Click for PDF

Early Modern Studies Journal

English Department | University of Texas | Arlington

The Hatted Woman and Her Unhurried History in Early Modern Ballads

Elizabeth Mazzola, The City University of New York

Introduction: Everywoman, Everywhere

Along with the radical ideas about women’s liberty, resilience, and practical savvy which surprisingly recur in many early modern ballads is the woodcut image of a hatted female figure, operating quickly and capably, her hat seeming to seal her up, keep her safe, and guard her on her way. Her exploits are vast, and her continued success extraordinary, even given the huge numbers of ballads produced in the early modern period, and sung, sold, and seen by probably everyone in London. To meet the extraordinary demand for these cheaply printed texts, publishers relied upon an inventory of stock stories with stock images, including among them our hatted female. Dressed for the streets and standing near a rose bush in many outings, she might be a nostalgic reminder of Tudor stability and Elizabethan greatness, but her clothing clearly marks her as a middle-class Carolingian woman.[1] She seems to hail from at least three different printshops in London and perhaps has her start in a West-Smithfield printshop headed by F. Coles; two other men with nearby shops and links to Coles found additional ways to keep this figure busy, profiting from an enlarging set of associations attached to her fleeing form.[2]

Woodcut images recycled in so many stories might be crude but they were not artless, and even if printers deployed them out of convenience, an audience’s rough, quick handling of a familiar form still required processing and care.[3] Certainly any stock images of stray females invited ballad audiences to rethink a woman’s places, her chances, and her reasons to move, as well as the many forces positioning her. Standing in a crowd and looking at a ballad stuck on the wall of an alehouse or nailed to a post outside, even viewers unable to read could nonetheless see a woodcut woman’s figure represented, often by herself and outside the household, denoted by clothing or a few choice possessions rather than by a husband, father, or brother. Threatened by violence, subject to bad weather, squeezed by a printer’s deadline or the size of a single ballad sheet, such female figures might appear alongside other figures but rarely interacted with them. They are not working or talking but occupying space autonomously and publicly.

Any apparent interchangeability of woodcut images also contributes to their meanings: the fact that a female figure denoting old age in one ballad could signal beauty and youth in another–or that the image of a woman who has fallen on hard times in one song portrays wealth and power in another–encourages audiences to reimagine representations of female experience, identity, and virtue. Those attributes that routinely gendered an early-modern body female–such as hair, beauty, fertility, complicity, clothing, silence—were depicted (and often downplayed) by a tiny collection of crude signs, and audiences were asked instead to consider other aspects of a woman’s identity. Even now, learning to read (or look at) ballads cultivates patience, reason, skepticism, and discipline: it sometimes requires learning how to wait or to watch, to understand meaning as something artfully assembled and, just as deliberately, broken apart

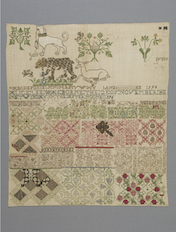

Such skills are especially useful in making sense of the sturdy iconography of our hatted female, her image reproduced in Figure 1. In many ballads where she appears, her figure lingers, dawdles, loiters, ambles—she isn’t being pushed or pulled but moves of her own accord. Sometimes in these texts her hat is a weapon, but more frequently it works like a thinking cap or an instrument to effect change.[5] We might add the hat’s function as a symbol of someone with the capacity for managing other symbols. Still other associations crowd around this hatted female form, though. Is it a stretch to link her with another hatted female, the figure called Mother Goose, closely associated with literacy and handily resembling the letter “A”? (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Some woodcut impressions of the hatted female figure (Cluster Id 61) included in The English Broadside Ballad Archive, dir. Patricia Fumerton (http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu).

Figure 2 Jolly Mother Goose. William Creswell from Seattle, Washington, USA, (1916), Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

The hard lines of the woodcut figure’s hat, hands, and dress not only smooth her way but also encourage us to view her exploits as something we should learn about. Literacy likewise involves Mother Goose’s exits and entrances along with our imagining good reasons for her to leave home in the first place. Although we’ve been schooled that character is fate, typography advances a diversity of paths to follow, and hatted women in other stories often take us far afield, as the encounters of the 18th century figure of Old Mother Hubbard (Figure 3) and the medieval travels of Chaucer’s Wife of Bath (Figure 4) tell us, too. Looking ahead, maybe Lily Bart’s failed career in a millinery shop is what ultimately dooms her.

Figure 3. The droll adventures of Mother Hubbard and her dog (1840). Even in nursery rhymes, hats confer power and register rebellion. Internet Archive Book Images, Wiki Commons.

Figure 4. In the Ellesmere manuscript, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath has red stockings, a gap-toothed smile, and a hat “as broad” as a shield; her “come hither” look is thus paired with a “Do Not Disturb” sign. Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4. In the Ellesmere manuscript, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath has red stockings, a gap-toothed smile, and a hat “as broad” as a shield; her “come hither” look is thus paired with a “Do Not Disturb” sign. Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Hatted women in many stories seem to collect meanings rather than get defined by them, and their regular journeys help us imagine female agency as something that flourishes with air, light, and speed. Few accusations of witchcraft taint the hatted woman’s adventures in these stories, including representations in early modern ballads.[6] Maybe the hat spares this figure, not only making sure her hair is neat but also keeping her skills sharp and aspirations intact.

Head Counts, Head Games, Head starts in Early Modern England

The work of costume historians like Aileen Ribeiro and Janet Ashelford investigating early modern accessories including detachable sleeves, belts, and gloves uncovers how these items of clothing can invite connection but impede movement; [7] hats, in contrast, seem to spur and legitimize movement, providing in many early modern ballads instruments for expertly handling space and managing encounters outdoors. Such equipment was especially important in early modern London. According to the calculations of ballad scholars like Tessa Watt and Patricia Fumerton, millions of ballad sheets were available to sixteenth and seventeenth century audiences, resulting in an extraordinary number of collisions of people with these texts every day.[8] The stories, songs, and lessons made available by cheap print took their place in a noisy, busy urban setting, such that reading or hearing ballads involved mobility and exposure as well as anonymity and membership in accidental, ephemeral communities. Stories about women that were shared in popular ballads often describe female experiences of being lost, hidden, or on the move in open spaces with sympathy, humor, and surprising admiration. Rarely are these female figures tamed.

When we put the work of Watt and Fumerton on ballad production and reception alongside research on the mobility of early modern urban women and what historian Laura Gowing calls “the freedom of the streets,”[9] we can grasp how opportunities for early modern women depended far less on patriarchal constraints and more upon an extended repertoire of behaviors and adventures permitted and even protected by a corresponding literacy of the streets. In multiple ballads, scores of unchaperoned women wriggle through standard classifications as wives, widows, and maids, evading the tags of scold, whore, or witch which, as Sarah F. Williams argues, inevitably characterized any early modern woman who rebelled.[10] Instead, these stories often outline and occasionally rationalize these figures’ unusual status, without coding or punishing their activities as criminal. If the hatted woman’s appearances across a wide array of stories challenge any assumption that popular culture is something uniform or homogeneous,[11] at the same time, we see few barriers to early modern freedom and equality on London’s streets. Chances to mix it up are ongoing. Just as remarkable is the way ideas about male power seem to explode or deflate in ballads about the women we find there. Feminism in early modern ballads stretches its muscles outdoors, sneaks up on men, or sometimes merely flows around them.

Still, the recurring woodcut image of a hatted female figure seems a riddle as well as a tool, the fact of her repeated sightings a puzzling sign of this figure’s ongoing triumphs and persistent well-being.[12] Despite being homeless, this hatted female figure finds a place in more than fifty broadside ballads housed in the Roxburghe, Euing, and Pepys collections I inspected. In this most ephemeral of printed texts, mass produced and extensively circulated, we meet her figure meeting us, unabashed and ready to move, unharmed by her travels. If she is an “Everywoman” of sorts, this figure is also a walking contradiction to early modern ideals of homely patience and maternal solicitude. Dislodged from the safety and predictability of indoor spaces, she presents herself at a crossroads when familiar daily experience is squaring off with the easily reproduced truths of cheap printed texts. So where is this figure going? Why isn’t she stopping? Which story gives her a home?

And what about that extra piece of print technology this image employs, the hat which goes where she goes? The hat’s unusual powers to conceal and to display are similarly explored by early modern genealogists, artists, and poets including Shakespeare, whose concern with headgear is strangely prominent in The Taming of the Shrew. Looking at Shakespeare’s plays, critics like Natasha Korda and Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass emphasize how clothing operates alongside other household goods and inside intimate settings, without considering how it might push people outside and away from others. Just as important as Christopher Sly’s undressing his wife for bed in The Induction to Shrew, however, is Petruchio’s obvious (and seemingly perverse) scorn for Kate’s cap, which seems designed, in contrast, to undress her for going outdoors.[13]

Two times, Kate’s cap is the subject of fierce negotiation, and some scholars have observed how Shakespeare’s preoccupation with early modern consumption and domesticity inform these scenes where Kate is taught to obey, show off, stand out, and disfigure herself with the aid of a cap which her husband despises. According to Petruchio, the cap Kate especially admires is “lewd” and “filthy,” a “baby’s cap” (4.3), a “bauble” (5.2)—and we are made to see how it works both on and off her head as a sign of taste and expensive commodity which Kate is finally willing to trash in order to please her difficult mate.[14] Yet such training may involve more than Kate’s learning how to dress. Shakespeare initially presents her as someone eager to be on her way, framing Kate’s ideas about the world’s justice, her father’s love, and her equivalence with her sister Bianca in a request for permission to leave. “I trust I may go, too, may I not?” Kate asks her father, opening her mouth in the hopes of opening a door (1.1.102). Her freedom of movement is something Kate prizes as much as the affection of a husband, and Petruchio not only recognizes both desires but also seems aware of hats’ own driving powers.

Seventeenth-century antiquarian Randle Holme registers the same awareness, devoting considerable attention to headgear in his 1688 Academy of Armoury, where he skillfully catalogues a variety of hats, hoods, turbans, caps, helmets, veils, and other “head tire” from images in the Bible, contemporary portraits, and evidence derived from Holme’s other work as a herald (see Figure 5).[15] If Kate clearly knows what kinds of caps gentlewomen wore, so does Randle Holme. But Holme also treats hats as armor for making one’s way in the larger world, enabling escape or guaranteeing safety, spiriting someone away but also, as examples like Shakespeare’s Kate attest, possibly authorizing this person’s power to authorize herself. This is why Holme puts women’s hats next to men’s hats in his Academy, and both objects alongside crowns.

Figure 5. Courtesy of the British Library Board. 137.f.7 The Third Book of the Academy of Armoury and Blazon, Book III, Chap V, Additions (page 246).

Many popular ballads share Holme’s fascination with objects that take women out of their homes and shield them in their travels, protecting and distinguishing them while also helpfully providing a degree of invisibility. Hats also assumed an important role in the new culture of looking and surveillance in which printed ballads obviously participated: learning how to look was undeniably crucial in an urban environment crowded by newcomers anxious to blend in, interpret signals, and navigate a tumult of signs and meanings which greeted them on the streets. As Rosemarie Garland-Thompson puts it, the “[d]isclocations” prompted by wage labor and urbanization “created anonymity, forcing people to rely upon bodily appearance rather than kinship or local membership as indices of identity and social position.” “Consequently,” she adds, “the way the body looked and functioned became one’s primary social resource as local contexts receded, support networks unraveled, and mobility dominated social life.”[16] Operating as “external organs,”[17] hats in print broadcast information quickly, but they could also efficiently block it, helping someone to stand out or hide out. They telegraphed legibility, not identity.

Small enough for a baby, regal enough for a king, hats in early modern ballads occasionally allow women to unmake themselves, too—to dissemble or hide or recombine parts of themselves. Hats also shadow smiles or scowls, or enable someone to look taller or larger, or transform age or class. More mysterious still, they are signs which insist that the woman who wears one is not a mere sign herself. In many of the ballads to which I now turn, the woman with a hat is magically freed from blame or endowed with special abilities, her hat a passport pushing her out of the household and into the wider world, happily out of reach of more established associations.

“A” is for “Abscond”

Jauntily heading out in so many ballads of the time, the hatted female figure appears in stories which introduce new regions for women to explore–where the hat seems to protect and secure her, sparing her from sin and absolving her of scandal and shame. Still, who knew early modern women could move about with such confidence, with so little in their way? Was Shakespeare’s Kate aware of such movements? Sealed up by her hat, this mysterious and ubiquitous ballad figure helps us piece together an early modern world where women might have chances to walk around or to walk away, where they could choose not to love and/or not to mother, to even to opt out of a future.

Ballads about this hatted figure also supply information about trade, famine, naval power, urban renewal, rural waste, employment prospects, illness, crude medicine, spectacular magic, babies, ghosts, courtesans, hangmen, crooks, sailors, and monarchs. If we really don’t hear much about far-off regions when we follow this figure’s lead, what she does provide instead is some elaboration of the ways that households could be upset by natural disaster as well as by lust or deceit. In some ballads, she takes flight suddenly: her vagueness appears to be a sign, a calculated effect, one step above a shadow. Multiplied over many years, hatted women appear prepared to stay outside, not hunted down by husbands or fathers, neither felled by anger nor trampled by terror. Their travels can involve wide crossings, for this figure bridges the textual with the visual, the home with outdoors, the learned with the unlettered.[18] Her secure status throughout is breath-taking, particularly given the way later stories of roving women often conclude with them being punished for running away–getting murdered or raped or left to die along some remote highway. Those later victims stay invisible, and recent statistics surrounding “femicide” often remain buried, too. But early modern ballads propose an alternative to these dreary pictures.[19]

At the start, we might note that this figure’s ubiquity aligns with the newly widened expanse of seventeenth-century literary experiments, including sonnets, biblical translations, fencing manuals, royal proclamations, songs, news stories, recipe books, and medical guides, all of them assembled and disseminated by the joint efforts of printers, editors, copyists, hawkers, and typesetters. Clearly, this figure has many places to visit, and no compelling reason to stay put.

Figure 6. “The Discontented Lover” Pepys Ballads. The Pepys Library, Magdalene College Cambridge. (EBBA 21034)

An early appearance in a ballad called “The Discontented Lover” (see Figure 6 above) reveals this figure arriving only to immediately disappear, her evanescence and elusiveness prompting her lover’s misery and ensuring his permanent captivity: “For glancing of that eye,/Which so lately did flye,/Like a Comet from the Sky;/Or like some great Deity:/But my wishes are in vain,/I shal never see’t again.”[20] Her image in this ballad “Printed for F. Coles” works perfectly as an introduction: this woman’s feet are on the ground, her hands are empty, and she has no baggage; the rose bush is a reminder, not a trap. What she embodies seems less important than what she avoids; she is exposed, but somehow can withhold. The boisterous companions with whom her lover ultimately surrounds himself are distractions from the difficult discoveries he makes as he pursues and then relinquishes his “divine” “Votress.” This speaker suffers, drowns his sorrows, and redirects his gaze at a “fair boon Company” gathered in a tavern, but the woman with the hat stays unblemished, “chaste as the Air” or “Holy Nunns breath in prayer.” Embracing the kinship that comes from “small Beer” and “[e]steeming no degree,” the speaker also finally disappears, blending in with the crowd, but not before issuing this forbidding farewell: “You Ladies adieu,/ Be your reckoning false or true,/ I am going forth to view,/What belongeth to all you.” Fumerton and Palmer (2016) emphasize this ballad’s depiction of “civil unrest,” but we might see the hatted figure as less of a casualty and more of a survivor (391), someone who marches forward while her besotted, sopping mate stays stuck inside.

Indeed, first appearing in the 1620s, this hatted figure is nearly everywhere in the 1660s and 70s, and then seems to retire in 1686. Later incarnations tend to bring and keep the hatted figure into view for longer periods of time, however. In “Loves fierce desire” (1644?), sold by F. Coles, the hatted woman Celia and her lover now address each other directly. The rose bush confirms the pastoral setting, where this woman displays more powers and is represented as an ideal match for the man, both of them endowed with “excellent wits” and “sutable minds.” Yet the woman also capably navigates danger, hiding in the woods as she waits for the man while remaining patient and unhurt, comfortably abiding there with Satyrs and Syrens:

Thy presence dear friend/ I have well understood,/ And how in exile/Thou has wandred the wood,/ But I am resolved/ thy sorrows to free,/ To make thee amends, / Ile soon come unto thee./ ‘Tis neither the Tyger,/ the wolf, nor the Bear,/ Nor shall Nylus Crocodile/ put me in fear,/ Ile swim through the Ocean/ upon my bear breast,/ To find out my Darling/ whom I do love best.[21]

Building on first impressions, F. Coles now uses the same woodcut image to deploy slightly different signals. If her motionless hands seem powerless and her body appears frozen in fear, this figure’s “breast” belongs to a “bear,” and as this ballad unfolds, we learn that she’s been piling up resources, preparing to act, the hat a sign of other strengths. She is confident and patient, and she trusts both her lover and the natural world. She tells the man that she has heard his complaints and that the power to return is entirely hers—it’s not that weather or misfortune or fright has separated them, in other words. In fact, she’s unusually comfortable outdoors and capable enough to repel “venomous creatures,” and she moves with speed when the time is right. The ballad concludes with an affirmation: “No doubt but each other/they will lovingly greet/ When as they together/do lovingly meet.”

Figure 7 “A warning for Married Women” Courtesy of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collection. Euing Ballad 377 (EBBA 31991)

This figure’s many appearances are both signaled and managed by her hat, and her agility, sexuality and appetites regularly command space in other ballads, sometimes even needing extra room. In “A Warning for Married Women” (1658-64?), printed for F. Coles, T. Vere, and W. Gilberston, we hear about Jane Renalds, a “West Country Woman” who marries another man after her lover, a “Sea-man brave,” is pressed into service and then presumed lost at sea (See Figure 7 above).[22] Jane has “three pretty Children” with her husband, a Carpenter, but one night a ghostly Spirit lures her away, although he must work hard to persuade Jane, who seems reluctant to leave at first: “If I forsake my Husband, and my little Children three;/ What means hast thou to bring me too, / If I should go with thee?” Jane is very practical about undertaking such a trip, and wants the rewards spelled out up front. The Spirit reports: “I have seven Ships upon the Sea,/ when they are come to Land,/ Both Mariners and Merchandize/ shall be at thy command.” The interim has apparently enabled the lover to amass a nice fortune, and so Jane, in leaving with him, is not simply fleeing her home but embarking on a new career as a magnate with the treasures the Spirit has promised her:

The ship wherein my Love shall sail,

so glorious to behold:

The Sails shall be of finest silk,

and the Masts of shining Gold.

Bereft of his wife, the Carpenter hangs himself, but the “pretty Children,” we hear, “heavenly powers./will for them well provide,” and so the hatted woman doesn’t need to look behind her. Shakespeare’s Celia famously describes banishment as liberty, but this female figure construes liberty in terms of property, commodity, and security, abandoning her household for an altogether different future when she trades her marriage for happiness on the open seas. The hat she wears is a sign of detachment then as well as evidence of a belief in her capacities for wealth and power–and her willingness to divest herself of small things in order to pursue greater returns. The hat loosens her from the household’s pettiness, signifies her desire to come into a larger fortune, and metonymically functions to signal the other objects she yearns for. This hatted woman works the margins, and when she speaks, it’s to open up an entirely different way of operating. The “Warning” thus operates more like a summons, for Jane finally imagines herself separated from her family, thriving in space apart and far away.

At the same time, the hat seems to insist on this figure’s inviolability, her tranquility and safety, something we can likewise detect in some illustrations from Wenceslaus Hollar’s Ornatus muliebris Anglicanus, or the Severall Habits of Englishwomen, from the Nobility to the country Woman, as they are in these times, 1640 (see Figures 8, 9, and 10).[23] Hollar represents multiple women in similar beaver hats who have no traffic with us, although they’re out in the world. Neither tied to momentous occasions nor attached to children or specific settings, these women own things and possess confidence, without belonging anywhere in particular.

Figure 8. Wenceslaus Hollar, 1640, Mulierus Anglicanum (The Clothing of English Women), Cleveland Museum of Art, CCO via Wiki Commons.

Figure 9. Wenceslaus Hollar, Civis Londinensis Vxor, 1643, National Gallery of Art, CC0, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 10. Wenceslaus Hollar, Ciuis Londinensis Melioris Qualitatis Vxor, 1643, National Gallery of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Hollar’s illustrations from the 1640s keep these women’s options open, but later ballads more frequently put the hatted figure closer to trouble or sin, handling her image more roughly. In “The Repulsive MAID” (1658-64?), also printed by Coles, Vere, and Gilbertson, the woman and her lover are counterparts once more, but this time primarily in dishonor and insult, pushing and pulling at each other with corresponding barbs and rude truths.[24] This ballad also puts the female figure indoors, strangely blocking the man’s way rather than moving freely herself, but her fixed position is a sign of integrity and deliberation. To be sure, the Repulsive MAID admits that, in in the past, she’s been more encouraging; “To open the door Love I have been bold,” she wryly acknowledges; now, however, ”another man hath [her] heart in hold.” Clearly what’s repellant are her decisions, not her attributes, and the male speaker keeps applying the pressure anyway: seeing her mind at work, he hopes to change it, not bypass it. Her intelligence makes her complicated, too, enabling her to regret her past offenses against her parents as well as see through this man’s faithlessness. She speaks to her “small friend” without anger, though, and uses the occasion of their meeting to represent her values as well as her knowledge about the lures of other women:

Maid: Alasse Sir I have found out your tricks;/ You love do crave of five or six,/ Yet take what you will/ It shall never me vex/ adieu for evermore.

Young Man: The Rose is red, and the leaves are green,/ And the daies are past which I have seen,/ Another man may be where I have been,/ for now I am thrust out of door.

This female figure is a force, her hat both a chimney and a screen which fires her up and makes her damage-proof. But I also think that the hat helps her see herself –as someone eager for sensation as well as for respect, an economic force, a member of the public sphere, a consumer, and a skeptic, prepared to hold out for a better offer or richer view. Age does not wither her, and her sometimes caustic comments do not repel future admirers, either.

Almost All the Single Ladies

Among the rest of the many ballads which might be included here are stories where the hatted woman is an ill-fated daughter, a mother, a much-married lady, and a speculator; she is proud, inventive, a bit of an escape artist but never really hiding; any setbacks do not stain her and only rarely do they detain her. Even when her figure appears in “A new ballad of King Edward and Jane Shore” (1671) (“Jane Shore” the name given to Elizabeth Lambert, a lower-class woman from the fifteenth century made infamous because of her liaisons with two kings), she remains untarnished.[25] Other than its being printed in 1671 London, we know little of this ballad’s origins, and stories of Jane Shore had been popular for decades when this ballad appears. Neither a wife nor martyr nor queen, she is instead someone who upsets these categories with her surprising transgressions and bottomless appetites, and yet, in this ballad’s catalog of “nasty women” associated with whoredom, the pox, murder, incest, treason, and poisoning, only Jane is not smeared. Her body is powerful, her attractions dangerous, but the ignominy attaches itself to the King, not to her:

“Hamlet’s incestuous mother, was Gertrude Denmarks Queen./ And Circe that inchanting Witch, the like was scarcely seen,/ Warlike Penthasillia was an Amazonian Whore,/ To Hector and young Tryalus, both of which did her adore,/ But brave King Edward who before had gained nine victories,/ Was like a bondslave fettered with Jane Shores all-conquering Thighs.”

The hatted woman “subdue[s]”, “command[s]”, and “enthrall[s]” two sovereigns, but she resurfaces in every stanza while the examples of mythical whores and classical strumpets are simultaneously trashed. Perhaps the hat rights Jane’s wrongs, or puts them in a more forgiving, even admiring light.

Figure 11 “A Lamentable Ballad” Pepys Ballads (EBBA 20242), The Pepys Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge

Without F. Coles’ oversight, the woodcut of this female figure occasionally faces harsher circumstances. This hatted woman is not so much discredited as repeatedly assaulted, for instance, in a handful of versions of “A Lamentable Ballad of the Ladies Fall” which first appear in 1674 and are reprinted throughout the 1680s (see Figure 11 above).[26] In this collection of stories, the hatted woman and her impoverished lover try to avoid her father’s censure by running off together after she becomes pregnant. Described as “beautious,” “gallant” and “lovely,” she is also courageous, offering to step “between the Swords/and take the harm on me” before proposing to disguise herself as a Page and wait for her lover “hard by [her] Fathers Park” so that the two of them can escape together. But he’s late for their meeting and, “succourless,” she returns home to die in childbirth, but not before she chews out her lover for his neglect: “Wo worth the time I did believe/ that flattering tongue of thine.” The baby dies shortly after its mother succumbs, and the lover kills himself upon learning of their tragic fate. There’s no reunion, no future, but also no sin that sticks, only a lesson for other “dainty Damosels” to “learn to be wise” and avoid “flattering words.”

What the “Lamentable Ballad” also seems to do, however, is lift the hatted woman’s image once and for all out of narratives about pain that is fatal, tragedy, and poor timing. Later ballads that make use of the same image describe more successful evasions of authorities and dismantling of households. This is particularly the case in “The young Man’s Resolution” (1678-80?), published by F. Coles, T. Vere, J. Wright, J. Clarke, W. Thackeray, and J. Passinger, a combination of handlers who emphasize the woman’s pluck and outspokenness. In this ballad, the male speaker encounters his “Sweet-heart” walking by herself, the way he is, in a grove. The two of them start talking, and at her request and promise of confidence, he itemizes all of the things which need to happen before he’ll marry, including usurers refusing good money, cats barking, and fishes feeding in green fields.[27] If his delay is tactical, the young woman is disheartened but not broken by these replies, and she dismisses his raillery with an eye to the prospects of women in general, announcing: “For if all Young-men were of your mind,/And Maids no better were preferred,/I think it would be when the Devil is blind/that we and our lovers should be marryed.” The reference to “our lovers” is pointed, I think: she indicates there’s no shortage of more compliant male partners, and maybe even an abundance of them. But there’s also a large pool of women who feel the way she does, and no wonder; after all—as other ballads with her image repeatedly show us—this woman can simply, confidently move on, with or without a man beside her.

And she does. The Bodleian collection includes several ballads that feature a similarly bemused, resourceful woman, with the same woodcut image nearly always the last in a row of four. She is a survivor, sometimes a relic, but still desirable and often domineering; indeed, the Bodleian catalog uses the codes of “Amorousness” and “desire” to classify her image. In the ballad titled “Ile never love thee more,” printed by J. Whitwood (date unknown), she resembles Shakespeare’s Dark Lady, with her lover bemoaning: “Why hath the Devil reign to . . . make me now his Imp/ That I that was thy constant friend,/ should now be called thy Pimp”? [28] This woman’s sexual appetites seem to blot out other features, but this crude assessment is really attached to the man’s suffering, not to the woman’s actions, and his closing words punish him, not her: “It seem[s] to me,/ Of every one so known:/ She never more should shine on me,/ I had rather lye alone.”

F. Coles, T. Vere, and J. Wright publish a similar ballad with the same woodcut in “A Good Wife, or None” (1663-74), and in their hands, it is a pitiful husband who registers this suffering.[29] More closely bound to this woman than the speaker in “Ile never love thee more,” this sorry narrator emphasizes his pain by underscoring the hatted woman’s powers and giving them biblical antecedents: “Yea, man was made for womans good./ Not idle like the drone/But for to heat and stir the blood/And not to lye alone.” F. Coles and his associates continue to manage the hatted figure’s potentially scandalous activities in “A Pleasant new Song betwixt a Saylor and his Love” (1674-79), where it is the husband who worries that the wife is cheating on him because he’s always away. But we’re also told that, despite his loyalty, his travels encourage her to stray: “From thy sight tho I were banisht,/Yet I always was to thee,/Far more kind than Ulisses /to his chast Penelope.”[30] Once again, the hero is commended for his constancy and devotion but the errant wife isn’t shamed or ultimately pinned down: her odyssey empowers and ennobles her, and this ballad closes with a kiss and the promise of a return to home.

Meeting Her Match

We can start to list some hypotheses here, for hats are regularly connected in early modern ballads to women who live in bodies that age and bleed and weep, but also run, hide, drink, swim, laugh, lust, and think. If hats sometimes signal displacement, they also locate women in specific situations where desire is capably managed at a local level, and sex takes place in a world which it accordingly transforms. Such details both lower the stakes and improve the outcomes, because these ballads focus on single episodes in much longer chains of events rather than emphasize a particularly fatal or tragic choice—they traffic in daring acts that aren’t criminal or even completely defining and involve little spilling of blood. Like a hat blown off by the wind or misplaced temporarily, unhappiness can easily be righted in these stories and happier fates pursued. And in just about all of these ballads, the hatted woman has in view some picture of betterment which she can obtain through her own efforts.

The woodcut image of the hatted woman thus gives us information about women’s lives as careers with extended histories, along with a set of attachments and collection of alliances. Widely available in print, such ideas have important consequences: even if some members of ballad audiences couldn’t read, they were taught how to understand literary conventions as well as how to be suspicious of them. What they come away with is the image of a hatted female figure who capably manages pain and defies gravity. The only things in her way are Tygers and time, not fear. She understands her body and is only rarely (if lamentably) frustrated by it. We might see the hat as a sign of stewardship of a self that is ready and prepared to act. In “The Maidens Counsellor” (1685-88), printed for P. Brooksby, this figure now becomes an elder, sharing her wisdom with young Damosels, reminding them that “A single life is free from care.” She herself is “twenty years and more” with “sweethearts store,” but she’s also mindful of the snares and stresses of married life, including the cruelty, cheating, swearing, and roaming of “Bad Husbands”–miseries unavoidable, our hatted speaker acutely observes, exactly because “poor Wives” “must stay at home.”[31] Future vistas are unclear in this ballad, but domestic comforts impossible.

Figure 12. “The Longing Shepherdess” Bodleian Library Douce Ballads 1 (119a).

F. Coles and his associates capitalize on this figure’s continued potential for flight in “The Longing Shepherdess, or LADY lie neer me” (1663-74), a pastoral song with an unusually lusty maiden, happy ending, and bonus image to finish off the song (Figure 12, above). Here, the maiden and lover map out a future filled with lovemaking and material wealth as well as the continued sharing of labor: “Do not Adonis like/Sweet-heart fly from me/For careful I will be/ as doth become me/Both of my flock and thine/while they are Reeding/Dear is my love to thee/As is exceeding.” Curiously, the version of success and companionship our female speaker describes might involve two hatted women, for the ballad includes another image of an extra woman who is carrying a child, alongside a man carrying a sack.[32] The middle figure of the hatted woman is not burdened, however: she appears ready to bolt, and at any rate is keeping her options open. In this ballad, the hatted woman has an equal as well as a forbear and a future; her child has a protector; and all of them find a clear path to travel.

Conclusion: The Undressing of the Shrew

Like Katherine Minola, the hatted woman in ballads refuses to be paraded about without a proper modicum of respect, and so we might thus see the cap which Shakespeare’s Kate prizes as more than just a bauble, even if she spends little time outdoors and seems finally resigned to take her humble place alongside other wives in the play at the end. But we should also be careful of trusting such appearances, as the ballad “?[c]onstance of Cleveland” (1674-79) takes similar pains to remind us (Figure 13). Published by F. Coles, T. Vere, J, Wright, and J, Clarke, the ballad reworks the story of the patient Griselda, pushing and twisting our sympathies by using the hatted female figure to illustrate competing forces. The story describes a love triangle involving a knight and a pair of women, one of them the jilted wife, the other the knight’s mistress, who is presented with the wife’s clothing and jewels. Her husband’s harsh treatment not only leaves the “virtuous” wife feeling sad but also, she claims, “unrespected” and anxious about her “right[s].[33] Who she is in her own eyes means something here, but the loss and gain of clothing and jewels outlined in the ballad prevent us from knowing which woman the woodcut image of the hatted female figure portrays, even when the wife is “big with child.” Maybe the vagueness of the hatted female figure’s image comes in handy, because the wife substitutes herself for her husband when he’s framed for a murder committed by his lover and “condemn’d to dye.” The king agrees to spare the husband if someone will trade places with him, and the wife volunteers but, moved by the spectacle of the married couple’s final embrace, Ruffions gathered around the Scaffold discover those really responsible for the murder. The ballad concludes with the execution of the wife’s murderous double, an ending which, we hear, “vertue” did “ bring to pass.”

Figure 13 “?constance of Cleveland” Pepys Ballads (EBBA 20223), The Pepys Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge

With its crude justice and tender ending, this ballad leaves other things unresolved, however. Is the last image at the top of this ballad page—our woman in the hat—an outcome, a reminder of what persists in a story of deceit and manipulation, or the opposite, a symbol of fidelity and constancy? The hat conceals identifying details, and the loving wife’s virtuous willingness to disappear provides a crucial resource. Maybe a good wife is ultimately also a loose woman, this ballad ironically, emphatically suggests. At the same time, the hat in “?[c]onstance of Cleveland” furnishes a tool which makes two women interchangeable—such that what protects one woman’s name sends another to her death. Yet we can also see the hat as signaling a system which allows one particular woman great freedom and rewards, but only if her strengths make other women disappear.

The same cultural machinery operates at the close of The Taming of the Shrew, where Kate’s extravagant speech suggests how she might be more like us than the sister and widow she leaves behind, “conferring by the parlour fire” (5.2.111). Once again, as our eyes fix on Kate, we are made to see a hat go on and come off her head. The cap she covets has proven to be something detachable, easily excised, ultimately trampled. But early modern ballads also intimate that such headgear symbolizes female resilience, patience, and autonomy, virtues which cannot be lost or relinquished, even when a hat is removed.

The ballad of Jane Shore emphasizes this lesson, and the careful marketing of F. Coles and his associates appreciates the teaching, too. Shakespeare’s Petruchio appears to absorb these ideas, as well. Petruchio never praises Kate’s hair or lips or her breasts; instead, focusing on her hat in two different scenes, he draws our attention to something external to her form, perhaps initially believing that, in removing it, he can change Kate or at least ground her. But another reading of the play’s final scene is made possible by the unstoppable movements of women which early modern ballads celebrate. Maybe Petruchio knows that even in trashing the hat once and for all, Kate will stay the same. And perhaps Kate now sees hats, like the caps, crowns, and other headgear Randle Holme catalogs, as part of a larger collection of signs she can sort through or think through, rather than as equipment she must have in order to successfully navigate her world.

This essay is based on a paper entitled “Hat Tricks: Dressing for Modest Success and Quick Egress in Early Modern Ballads,” to have been presented at the 2021 meeting of The Renaissance Conference of Southern California, and I want to acknowledge the extraordinarily generous help of Barbara Mello, who helped me recast the argument. Aileen Ribiero provided crucial information at a very early stage, and detailed comments provided by Amy Tigner were of enormous help at a later stage. I also want to thank EMSJ’s two anonymous readers for their shrewd and generous suggestions.

[2] My cursory forensic investigation works with the inventories of the Bodleian Libraries Broadside BalladsOnline http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/ and the USCB English Broadside Ballad Archive, directed by Patricia Fumerton. http://ebba.english.uscb.edu. “J. Passinger” and “P. Brooksby” seem to have worked with men who worked with F. Coles, including a “W. Thackeray” and a “J. Clarke,” but I’m unable to explain how Whitwood fits into the picture, or even speculate whether the woodcut image was borrowed, stolen, copied, or simply showed up in new settings. Patricia Fumerton and Megan E. Palmer provide additional facts about her provenance and possible political affiliations, however. They posit that there were possibly one or two single cuts of this image and count up eleven extant prints and at least seven different wooden blocks (399 n15). Calling her figure “The Welcoming Woman,” they also carefully explore the contradictory details of Tudor rose and fashionable Carolingian dress, emphasizing this figure’s nostalgic appeal as an emblem of dynasty and royalty,particularly during a time of civil unrest. See “Lasting Impressions of the Common Woodcut” in The Routledge Handbook of Material Culture in Early Modern Europe eds. Catherine Richardson, Tara Hamling, David Gaimster(NY: Routledge, 2016): 383-400 (see esp. 387-91). Fumerton and Palmer also cite the work of Christopher Marsh,who treats a related figure, the woodcut image of a middle-class man who shows up in some of the same balladswhere the hatted female figure appears, in “A Woodcut and its Wanderings in Seventeenth Century England.” The Huntington Library Quarterly 79, 2 (2016): 245-62. Marsh notes that Coles, Brooksby, Passinger, and Whitwood alldeployed this man’s figure (249 n10), and perhaps this male figure was the one who escorted—or accompanied—“The Welcoming Woman” into their printshops.

[3] Theodore Barrow complains that early modern woodcut images were “generic to the point of being meaningless”in “From ‘The Easter Wedding’ to ‘The Frantick Lover.’” Studies in Ephemera: Text and Image in Eighteenth Century Print (Lewisburg: Bucknell UP, 2015): 291-40. Natascha Wurzbach similarly describes them as a “crude affair” with “little illustrative function” in The Rise of the English Street Ballad, 1550-1650. Trans. Gayna Walls (NY: Cambridge UP, 1990). 9. In contrast, Tessa Watt describes “stock ballads” in which “stock images” might play a useful role. See Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (NY: Cambridge, 1993). Such recycling was useful rather than meaningless, Watt proposes, arguing that “literacy and print were not only ‘agents of change” “but could also be forces for cultural continuity” (330). Other scholars make even larger claims for the importance of re-using ready-made images: repurposing bred familiarity and tamed what was otherwise disorderly. As Patricia Fumerton puts it, for instance, in making use of “infinitely arrangeable bits and pieces”—including recycled tunes, images, and narratives—popular ballads described and replicated the “unsettled” nature of urban life. See “Remembering by Disremembering” EMLS (2008) para 10, now expanded in The Broadside Ballad in Early Modern England: Moving Media, Tactical Publics (Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania Press, 2021). Related observations are provided by Fumerton and Palmer (2016) 383; Clare Backhouse and Angela McShane, “Top Knots and Lower Sorts: Print and Promiscuous Consumption in the 1690s.” Printed Images in Early Modern Britain: Essays in Interpretation. Ed. Michael Hunter (NY: Routledge, 2010): 337-58; and Katie Sisneros, “Early Modern Memes: The Use and Re-Use of Woodcuts in 17th Century Popular Prints.” The Public Domain Review https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/early-modern-memes-the-reuse-and-recycling-of-woodcuts-in-17th-century-english-popular-print accessed 2 July 2022

[4] See Fumerton 2021. As important as distinguishing the letter “G” from the letter “C,” for instance, could be figuring out whether the woodcut image of a girl holding flowers represents a maid being courted or a prostitute with a gift, someone in mourning or an emblem of pastoral retreat. Shakespeare appears to toy with this rich visual tradition as well as in the characters of Ophelia and Perdita, where the ambiguity of the visual imagery surrounding them is perhaps its most important attribute. Shakespeare often seems to delight in the confusion, putting Perdita next to her mother’s marbled form or making sure Bianca crosses paths with Kate, such that being a member of Shakespeare’s audience means deciphering visual cues, even ignoring likenesses. See Listening to Images (Durham, Duke UP, 2017), where Tina M. Campt describes the ways looking might involve listening, waiting for a hum or buzz, the sound of “recalcitrance” (4) or “quiet” “tension” (50), trying to discern evidence of “restraint” or the “labored balancing of opposing forces” (51), some signal of resistance to the ordering impulses of the artist. In a recent project on Macbeth, I explore this resistance in terms of the ways an early modern mass public might respond to directions to attend, ignore, or distrust the information the character Ross provides.

[5] The witch’s hat, royal crown, tiara, wedding veil, mortarboard and helmet are all part of a larger collection of ritual objects which include the nun’s veil, the cowl, miter, and the hood—even a wig, as Drake Stutesman exploresin Hat: Origins, Language, Style. (London: Reaktion Books, 2019). Stutesman argues for the hat’s “almost unparalleled iconic status. It stands for religion, for governance, for militia, for custom, for tradition, for beliefs, for trade, for clan, for fashion, and for entertainment” (20). Beverly Chico makes the case that hats are “material communications” denoting gender, age, social status, and group affiliation in “Hats, Women’s.”Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, ed. Valerie Steele, Vol. 2. (NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2005): 181-85. Gale eBooks. Accessed 2 September 2021. See, too, Penelope J. Corfield, “Dress for Deference and Dissent: Hats and the Decline of Hat Honor.” Costume 23, 1 (1989): 64-79. “Proverbially,” Corfield nicely observes, “hats are eaten, passed around, talked through, thrown into the ring or, simply, hung up” (75). And things change, of course, “at the drop of a hat.”

[6] Despite the prevalence of witches’ hats in 17th century pamphlets, there are relatively few ballads about witchcraft, and rarely do they feature the pointed, conical hat.

[7] Excellent discussions of early modern dress and fashion are provided by Aileen Ribeiro, Fashion and Fiction: Dress in Art and Literature in Stuart England (New Haven: Yale UP, 2006); and Jane Ashelford, The Art of Dress: Clothes Through History, 1500-1914 (National Trust, 2011). Ashelford concentrates primarily on men’s fashion, possibly because the upper-class habits she emphasizes kept women mostly indoors, their portraits representing them in informal attire or states of “undress” (98). Outerwear similarly counts for less in Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory (Cambridge UP, 2001), where Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass focus on accessories like sleeves, belts, gloves, and jewels rather than on hats, describing clothing which can be traded or detached but also exposed or exchanged within more intimate, indoor settings. Jones and Stallybrass suggest that Othello’s handkerchief generates considerable anxiety because it keeps getting lost (85); perhaps hats, in contrast, generate less anxiety (or avoid intense scholarly discussion) because they enable people to get lost.

[8] See Watt 11. Some of the implications of Watt’s numbers have been recently explored by Fumerton (2021) ,36.

[9] Laura Gowing, “’The freedom of the streets’: women and social space, 1560-1640.” Londonopolis: Essays in the Cultural and Social History of Early Modern London. Ed. Paul Griffiths, et al. (Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000):130-51. As Gowing puts it, a “particular kind of urban femininity was being constructed around the social and cultural shifts of high migration, economic pressures, changing civic cultures, an expanding domestic service sector, and changing patterns of consumption” (130).

[10] See Williams, Damnable Practices: Witches, Dangerous Women, and Music in Seventeenth-Century English Broadside Ballads (NY: Routledge, 2015) 3. Some of Williams’ ideas about ballads and rebellious women are first introduced in “To the Tune of Witchcraft: Witchcraft, Popular Song, and the Early Modern English Broadside Ballad.” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music (2013).

[11] In a related discussion, Zachary Lesser explores how assumptions about the black-letter typeface typically used in ballads restrict both our readings of cheap texts and our awareness of the extent of their audiences. See “Typographic Nostalgia: Playreading, Popularity and the Meanings of Black Letter.” The Book of the Play: Playwrights, Stationers, and Readers in Early Modern England. ed. Marta Straznicky (Amherst: U Massachusetts Press, 2006: 99-126 (100). Lesser’s insights help us imagine how the recycling of the familiar image of the hatted woman might prove an “excellent marketing strategy” for our West-Smithfield publishers, a way to cater to their audiences by making them hungry where most they were satisfied (see 106). I thank an anonymous reader of EMSJ for directing me to Lesser’s invaluable work.

[12] See Fumerton and Palmer (2016) 387.

[13] See Natasha Korda, Shakespeare’s Domestic Economies: Gender and Property in Early Modern England (Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania Press, 2002). Jones and Stallybrass comment on Sly’s behavior without referring to any similarities with Petruchio’s sartorial surveillance (214-25). In Shakespeare’s Speaking Properties (Lewisburg, Bucknell UP, 1991), Frances N. Teague refers to the comical stage business surrounding Grumio’s cap, but curiously makes no mention of Kate’s headgear. For an overview of the ways clothes are traded, worn, and trashed in this play, see Emma Smith, “Clothing and Transformation in The Taming of the Shrew” https://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/clothing-and- transformation-in-the-taming-of-the-shrew downloaded 2 July 2021; and Kelly N. O’Connor, “Fine Array and Mean Habiliments.” Shakespeare Newsletter 57, 1 (2007)

[14] This, and all citations from The Taming of the Shrew, are taken from Shakespeare, William, et al. The Norton Shakespeare. Third edition (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015).

[15] Holme’s attention to fashion is mentioned by Ribiero 9; Jones and Stallybrass 86; and Korda 5-6. For an overview of Holme’s work, see Living and Working in Seventeenth Century England: An Encyclopedia of Drawings and Descriptions from Randle Holme’s Original Manuscripts for the Academy of Armoury (1688). Eds. N. W. Alcock and Nancy Cox (British Library, 2001). See also the British Library website devoted to Holme at https://www.bl.uk/picturing-places/articles/the-manuscript-remains-of-the-randle-holmes-herald-antiquaries-of- the-17th-century. In a private communication (28 December 2019), Professor Ribiero directed me to her 2005 book and also pointed out that the hatted woman in numerous early modern woodcuts appears to wear the beaver hat initially worn by elite women when riding; Ribiero claims this hat becomes more widely worn by non-elite women starting in the mid-17th century. Jones and Stallybrass briefly mention the wide-brimmed men’s beaver hat in Renaissance Clothing (53). See also Clare Backhouse, Fashion and Popular Print in Early-Modern England: Depicting Dress in Black Letter Ballads (London: I.B. Tauris & Co., 2017). Backhouse persuasively argues that fashion supplies evidence about mobility, the streets, and surveillance—what Rosemarie Garland-Thompson describes in Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (NY: NYU Press, 1996) as a new culture of looking. Megan Palmer provides an excellent guide to early modern dress as featured in contemporary ballads in the Ballad Illustration Archive Costume Book. https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/page/early-modern-costume.

[16] Garland-Thompson 12.

[17] Jones and Stallybrass use this term in their discussion of the early modern glove as a fetish, coated with desire—unlike the hat, perhaps, covered in dust. See “Fetishizing the Glove in Renaissance Europe” Critical Inquiry 28, 1 (2001): 114-32 (116).

[18] Fumerton and Palmer (2016) mention these opposing tendencies (387-90).

[19] The contrasts with later biographies of women are numerous and often dismaying. See, for example, Saidiya Hartman’s discussion of the “futureless careers” of “surplus” women who “defy gravity” in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (NY: Norton, 2019). Hartman’s discussion is eloquent, painful, but always optimistic; in contrast are Vanessa Veselka’s reflections in “The Green Screen: The Lack of Female Road Narratives and Why it Matters.” The American Reader 1, 4, where she writes: “By 2004, so many women had been found dead along the interstates that the FBI started the Highway Serial Killers Initiative to keep track of them. . . When a man stops onto the road, his journey begins. When a woman steps onto that same road, hers ends.” Elsewhere, Veselka notes, in modern-day storytelling “a woman on the road is marked. She has been cut from the social fabric, excised at such an elemental level that when she steps onto the road, she steps into an abyss.” See https://theamericanreader.com/green-screen-the-lack-of-female-road-narratives-and-why-it-matters.

[20] “The Discontented Lover.” Magdalen College-Pepys Ballads 3.38 EBBA 21034. “Printed for F. Coles, in Wine-Street.” http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/21034/citation. For access to this and many of the other ballads discussed here, see The English Broadside Ballad Archive, dir. Patricia Fumerton. Subsequent citations to this archive will be abbreviated EBBA. Fumerton and Palmer use this ballad as an example of the “civil unrest” the “Welcoming Woman’s” figure often signifies, and they contrast her “saintly” figure here with the “degradedkingdom” pictured at the song’s close (391).

[21] “Loves Fierce Desire.” British Library-Roxburghe C.20.f.9.130-131. EBBA 30440. “Sold by F. Coles, in Wine- Street.” http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/30440/citation

[22] “A Warning for Married Women.” University of Glasgow Library-Euing Ballads 377. EBBA 31991. https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/31991/citation. “Printed for F. Coles, T. Vere, and W. Gilbertson.”

[23] I thank Aileen Ribiero for directing me to Hollar’s work.

[24] “The Repulsive Maid.” British Library-Roxburghe C.20.f.9.214-215. EBBA 30864. “Printed for F. Coles, T. Vere, and Gilbertson.” http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/30864/citation

[25] “A new ballad of King Edward and Jane Shore.” British Library-Roxburghe.C.20.f.9.258 EBBA 30969.https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/30969/citation. “1671 London, Printed.” For an overview of the role of Shore’s narrative in seventeenth-century literature both high and low, see Richard Helgerson, “Weeping for Jane Shore.” South Atlantic Quarterly 98, 3 (1999): 451-76. Helgerson argues that Shore’s story is a transformative one: “[T]hrough the shaping power of its extraordinary emotional appeal,” it “rema[de] the generic map of English literature” (451), linking tragedy with domestic comedy, and chronicle history with palace intrigue. We might claim something similar for the hatted female figure’s woodcut image. She seems to go wherever she wants, never ruined by disaster nor able to completely avoid it: Jane’s errant figure is a useful tool, not a crushed one. Fumerton and Palmer (2016) similarly describe this ballad as an attack on Charles II’s indiscretions (393); andMarsh explores the oft-sighted male figure’s image in this ballad (252-54).

[26] “A Lamentable Ballad of the Ladies Fall.” Magdalen College-Pepys Ballads 1.510-511. EBBA 20242 https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/20242/citation. “Printed for W. Thackeray and J. Passinger.” Williamsexplores how ballads about witchcraft appropriated this melody (without making use of the image) in “Witches, Lamenting Women, and Cautionary Tales: Tracing the‘Ladies Fall’ in Early Modern English Broadside Balladry and Popular Song.” Gender and Son in Early Modern England. Eds. Leslie C. Dunn and Katherine R. Larson (NY: Routledge, 2014): 31-46.

[27] “The young Mans Resolution.” National Library of Scotland-Crawford. EB.114 EBBA 32770. The publishers listed are “F. Coles, T. Vere, J. Wright, J. Clarke, W. Thackeray, and J. Passinger.” https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/32770/citation

[28] “Ile never love thee more.” Bodleian Library Douce Ballads 1 (101b). “Printed by W. Whitwood.” http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/view/sheet/4216

[29] “A good wife, or none.” Bodleian Library 4o Rawl 566 (198)r http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/view/edition/1897 The publishers listed are “F. Coles, T. Vere, J. Wright.”

[30] “A pleasant new song” Bodleian Library 4o Rawl 566 (188) http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/view/sheet/2301 The publishers listed are “F. Coles, J. Wright, J. Clarke.”

[31] “The Maidens Counselor.” Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library 2000 Folio 6 149. EBBA 35813. “Printed for P. Brooksby.” https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/35813/citation

[32] “The longing shepherdess” Bodleian Library Douce Ballads 1 (119a). http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/view/sheet/29812 The publishers listed are “F. Coles, T. Vere, J. Wright.” Watt briefly refers to the last image of two hatted women in discussing a ballad about the early sixteenth-century Protestant heroine, the Duchess of Suffolk (91-93).

[33] “?[c]onstance of Cleveland.” Magdalen College-Pepys Ballads 1.476-477 EBBA 20223. http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/20223/citation http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/20223/citation The publishers listed are “F. Coles, T. Vere, J. Wright, J. Clarke.”